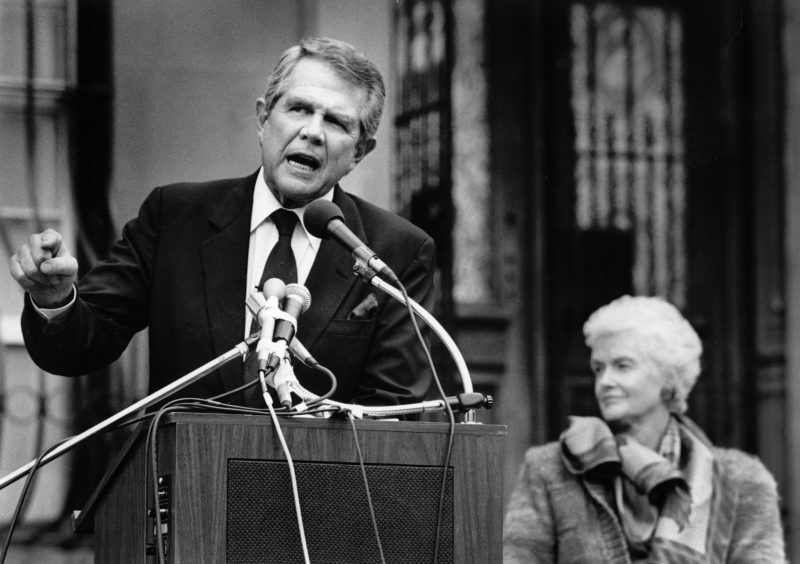

The Rev. Pat Robertson, a Baptist preacher who attracted a worldwide following as a religious broadcaster, built a business empire from his headquarters in Virginia Beach and helped create a powerful political movement of religious conservatives as a founder of the Christian Coalition, died June 8 at his home in Virginia Beach. He was 93.

The Christian Broadcasting Network, which Rev. Robertson founded, announced the death but did not provide a cause.

Rev. Robertson, the son of a long-serving U.S. congressman and senator from Virginia, was among the first evangelists to take religion out of the realm of private belief and into the secular arena of politics. In large part through his influence, the Christian right became a potent force in American politics and culture.

His sole foray into electoral politics, a short-lived effort to seek the Republican presidential nomination in 1988, “signaled the modern melding of fundamentalist Christianity with the Republican Party — an association that has continued right up to the present day,” Larry J. Sabato, a politics professor at the University of Virginia, told The Washington Post.

Unlike many evangelists, Rev. Robertson came from a privileged background. He grew up in the corridors of power in Virginia and Washington and graduated from Yale Law School before turning to the ministry in the late 1950s.

“Robertson’s critics often depict the evangelist-broadcaster as a political extremist with bizarre beliefs,” novelist and journalist Garrett Epps wrote in The Post in 1986. “But it may make more sense to view him as the last old-school southern politician.”

Cherubic-looking, with a soothing, conversational manner even when making incendiary remarks, Rev. Robertson reached millions of people through his Christian Broadcasting Network, which he founded on a shoestring budget in 1960. For decades, he had a powerful spiritual and political impact on a far-flung audience of “born-again” followers.

Although he bristled at the term televangelist, Rev. Robertson was one of the most popular and influential religious figures of his time. For decades, he was the host of “The 700 Club,” a casual talk show that combined hard-right politics, faith healing and lifestyle news. Broadcast in dozens of languages and in more than 200 countries, the show made Rev. Robertson the world’s most-watched TV preacher.

“There have been many media-savvy, politically active preachers in American history,” Sabato said, “but Pat Robertson eclipsed all his predecessors by combining impressive television skills and small-donor fundraising with a presidential candidacy that had a substantial impact.”

In addition to his TV programs, Rev. Robertson made public appearances and produced dozens of books and videos as he built a business empire that brought in more than $300 million a year at its height.

He expanded his mission to education in the late 1970s, founding CBN University (later renamed Regent University) in Virginia Beach with the aim of “training Christian leaders to change the world.” Former Virginia governor Robert F. McDonnell (R) was a graduate of Regent’s law school, and hundreds of alumni worked in the administrations of presidents George W. Bush and Donald Trump.

Rev. Robertson was a vocal supporter of Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and, after Trump was elected, interviewed him at the White House. He distanced himself somewhat after Trump lost the 2020 presidential election to Joe Biden, saying Trump exhibited “very erratic” behavior and inhabited an “alternate reality.”

Seeking to encourage conservative Christians to become active in public life, Rev. Robertson helped launch several advocacy groups, including the American Center for Law and Justice, which was designed to be a conservative counterpart to the American Civil Liberties Union.

In 1987, Rev. Robertson was one of several founders of the Christian Coalition, which aimed to spur evangelical Christians into political action. Among other things, the group distributed voter guides in churches, outlining its preferred candidates — virtually all of them Republicans.

When Rev. Robertson sought the 1988 GOP presidential nomination, he hoped to build a government run by what he called “Spirit-filled Christians.”

“I don’t think being a Christian means just spending time in the confines of the church, behind stained-glass windows, singing hymns,” he said, adding that God had told him to run.

He had a deeper campaign war chest than any candidate except the eventual president, George H.W. Bush, but members of his old Marine Corps unit — including former congressman Pete McCloskey (R-Calif.) — came forward to say he had exaggerated his record in the Korean War. Rev. Robertson filed a $35 million slander lawsuit against McCloskey but later dropped it.

Rev. Robertson finished ahead of Bush in the Iowa caucuses, but the embarrassing episode over his military record helped derail his campaign, and he quit the race after running poorly in the early primaries. Nevertheless, his candidacy heralded the rise of religious conservatives in politics.

“In the not-too-distant past, the charismatic and Pentecostal wing of American Protestantism saw political engagement as a ‘worldly’ and sinful activity,” the late Michael Cromartie, who was vice president of Washington’s Ethics and Public Policy Center and a longtime watcher of the evangelical movement, said in a 2011 interview with The Post. “Pat Robertson, perhaps more than anyone in the charismatic wing of conservative Protestantism, was pivotal in creating this paradigm shift.”

After his flirtation with the presidency, Rev. Robertson reverted to his self-appointed role as “God’s prophet.” He often predicted doom for those he deemed insufficiently righteous and attributed natural disasters and other calamities to perceived political and moral failings. He insulted other religions and had a long history of divisive statements that created international friction.

In 2005, Rev. Robertson called for the United States to assassinate Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. The evangelist later apologized, after a fashion.

“Wait a minute,” he said, “I didn’t say ‘assassination.’ I said our Special Forces should ‘take him out,’ and ‘take him out’ can be a number of things, including kidnapping.”

When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005, Rev. Robertson suggested that the storm was God’s punishment for legal abortion. He attributed the Haitian earthquake in 2010 to “a pact with the Devil” made two centuries earlier, when the nation’s Black founders won their independence from French enslavers.

Rev. Robertson supported Israel, but in his 1991 book “The New World Order,” he repeated long-discredited notions that a cabal of Jews and Freemasons secretly controlled much of American life. He denounced Hinduism as “demonic” and Islam as “not a peaceful religion.” He claimed that some Christian denominations harbored “the spirit of the Antichrist” and said Mormon beliefs “are, to put it simply, wrong.”

He called feminism “a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians.”

After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Rev. Robertson said he agreed with fellow Virginia minister Jerry Falwell that nonbelievers, abortion providers, feminists and gay people in the United States were as blameworthy as the Muslim extremists at the controls of hijacked airliners.

Ultimately, Rev. Robertson’s provocative comments and condemnations of what he considered rampant moral depravity pushed him to the cultural margins.

“Republicans began to shy away from seeking his public endorsement,” Sabato told The Post. “Robertson’s backing was successfully used by Democrats to brand his candidates as ‘extreme’ and ‘religiously intolerant.’”

Marion Gordon Robertson was born March 22, 1930, in Lexington, Va. He acquired his nickname, Pat, from an older brother who liked to pat young Marion’s cheeks.

His parents were the children of Baptist pastors, and Rev. Robertson often boasted of his patrician roots. He said he was descended from two presidents, William Henry Harrison and his grandson, Benjamin Harrison.

Many of Rev. Robertson’s political and religious ideals were shaped by his father, Absalom Willis Robertson, who served seven terms in the House as a conservative Democrat from Virginia, then was a senator from 1946 to 1966.

“I learned to say ‘Mommy,’ ‘Daddy’ and ‘constituent,’ in that order,” Rev. Robertson often said.

He worked on his father’s early campaigns, but during a hard-fought race in 1966, Rev. Robertson stayed on the sidelines, telling The Post 21 years later: “The Lord steadfastly refused to let me.”

His father narrowly lost in the Democratic primary and became, in Rev. Robertson’s words, “a broken, defeated man.”

After attending public schools in Washington, Rev. Robertson graduated from the McCallie School, a private prep school in Chattanooga, Tenn.

He returned to his hometown of Lexington to attend Washington and Lee University, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society before his graduation in 1950. He served as a Marine Corps officer during the Korean War before enrolling at Yale Law School in 1952.

He admitted to a somewhat reckless youth, filled with drinking, poker, a succession of girlfriends, frequent visits to New York nightclubs and a wild-oats period in Europe.

In 1954, against his parents’ wishes, he married Adelia “Dede” Elmer, a Catholic from Ohio. They celebrated their anniversary on March 22, but in 1987 the Wall Street Journal revealed that they were actually married five months later, on Aug. 27, 1954.

Although Rev. Robertson often railed against premarital sex as a preacher, his wife was more than six months pregnant when they were married.

Dede Robertson died in April 2022. Survivors include four children, Timothy Robertson, Elizabeth Robinson, Ann LeBlanc and Gordon Robertson; 14 grandchildren; and 23 great-grandchildren.

Rev. Robertson graduated from Yale Law School in 1955 but failed the New York bar exam and never practiced. Instead, he became a management trainee and lived in the New York City borough of Staten Island, where he was chairman of the 1956 presidential campaign of Democrat Adlai Stevenson.

By the late 1950s, Rev. Robertson was drawn to the Pentecostal and fundamentalist elements of Christianity, following the path of his mother, who became increasingly reclusive and prayerful.

After what he called a revelatory moment, in which he claimed to be “speaking in tongues,” Rev. Robertson enrolled in what is now the New York Theological Seminary, from which he received a master of divinity degree in 1959.

He moved his family to Portsmouth, Va., and later was ordained as a Baptist minister. With only $35 in the bank, he borrowed $37,000 to buy a failing television station in Portsmouth, soon finding his new path as a religious broadcaster.

In 1966, when Rev. Robertson needed $7,000 to meet his monthly expenses, he held a telethon, asking for 700 viewers to pledge $10 a month. His successful plea marked the beginning of “The 700 Club.” The program’s format, combining testimonials of faith with discussions of current events, was considered revolutionary for its time.

A popular early host was Jim Bakker, who had a religious puppet show with his wife, Tammy Faye. Their tearful appeals helped the station garner donations from viewers until the Bakkers left to begin their own ministry in the early 1970s. Their televangelism empire, known as the PTL Club, collapsed in the 1980s amid a lurid sex and financial scandal.

After Bakker’s departure, Rev. Robertson took over as “The 700 Club” host, interviewing guests and praying with callers. In the 1970s, CBN became one of the first networks to expand into satellite and cable broadcasting, a move Rev. Robertson said was ordained by God. He often noted that he sought divine guidance in his business affairs.

Whatever the source, Rev. Robertson proved to have remarkable skills at broadcasting and moneymaking. CBN regularly had more than 40 programs in production, with global broadcasts in more than 70 languages.

As Rev. Robertson’s media and real estate holdings expanded worldwide, his net worth was estimated by Forbes magazine at more than $100 million. (Others speculated that the true figure was much higher.) He lived in a neo-Georgian mansion, kept a stable of horses and owned a private jet.

Some of his business deals raised legal and ethical questions. Among his extensive commercial interests in Africa, he had agreements with dictatorial rulers Charles Taylor of Liberia and Mobutu Sese Seko of Congo (formerly Zaire) that gave Rev. Robertson’s companies mining rights for gold and diamonds. The Virginian-Pilot newspaper of Norfolk reported in 1997 that Rev. Robertson’s humanitarian organization, Operation Blessing, had been used to transport equipment to Africa for diamond mining.

In 1990, Rev. Robertson created a holding company, International Family Entertainment, and reestablished CBN as a nonprofit charity. His son Gordon P. Robertson became CBN’s chief executive in 2007 and replaced his father as host of “The 700 Club” in 2021.

The Family Channel, as the holding company became known, proved to be a cash cow and was sold in 1997 to one of Rupert Murdoch’s Fox broadcasting divisions for $1.9 billion. Rev. Robertson and his family reportedly netted $227 million from the deal.

The channel was later purchased by the Walt Disney Co. One condition of the sale was that, regardless of any changes of ownership, Rev. Robertson’s “The 700 Club” would air twice a day in perpetuity, keeping his face and message before the public for eternity.