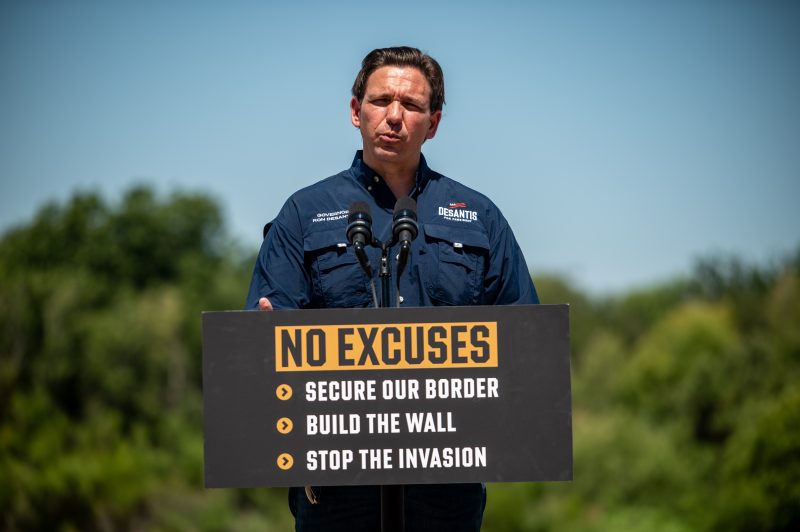

Former president Donald Trump proposed a naval blockade of Mexico. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis pledged to send drones and Special Forces over the southern border starting “on day one.” And investor Vivek Ramaswamy imagined launching a “shock-and-awe” military campaign against drug cartels.

Republican candidates are engaged in a rhetorical arms race, vying to one up each other with tough talk on the U.S. border with Mexico, taking the 2016 rallying cry of Trump to “build the wall” to the next level. The bellicose proposals reflect widespread Republican outrage over immigration, as well as the ongoing crisis of opioid deaths. “It’s now time for America to wage war on the cartels,” Trump said in a campaign video.

But Mexican officials and independent security analysts have cautioned that military force by the United States would fail to quickly stop drug trafficking while torching relations with its southern neighbor and risking significant casualties.

“I understand the political appeal of holing out one of these guys at 50 yards,” said Justin Logan, director of defense and foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “It is not a 1950s Western with guys in white hats and guys in black hats. It is a very serious and tricky problem that is tough to solve with a hammer. You could wind up with an awful lot of bloodshed on the border and plenty of fentanyl to go around, which would be the worst of all possible outcomes.”

The Republican candidates frequently frame their eagerness for warfare on the southern border in contrast to more far-flung military entanglements, particularly in Ukraine, as Republican support for a prolonged commitment there shows signs of waning.

Despite widespread public disenchantment with the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Republican proposals now often draw on those conflicts as models for strikes in Mexico. Trump compared attacking drug cartels to the 2017 campaign against the ISIS terrorist group, and Ramaswamy referenced the assassinations of al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in 2012 and Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in 2020.

Security analysts said those proposals rely on a misguided idea of how drug trafficking works in Mexico. Falko Ernst, a Mexico analyst for the International Crisis Group, said that comparisons to combating ISIS are wrong. Those Islamist militants were imposed from the outside.

Mexican traffickers, in contrast, are often deeply embedded in their communities. Republicans have “the illusion you have a clearly delineated threat” in Mexico that “stands apart from the rest of society, politics and the economy, one that can be surgically removed, a cancer-like growth in the body,” Ernst said. “It just doesn’t work that way.”

Mexican officials have reacted angrily to the Republican proposals to unilaterally enter their country’s territory. “We’re not going to be anybody’s piñata,” President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said last month after DeSantis made his comments in the first Republican primary debate about deploying Special Forces against Mexican fentanyl producers.

The Republicans want “to come over and hunt for narco traffickers, violating our sovereignty, something we are never going to allow,” López Obrador said in his daily news conference. He has also said he would urge Americans of Mexican origin to vote against Republicans if their “aggression” continued.

In April, Marcelo Ebrard, at the time the Mexican foreign minister, told The Washington Post that a U.S. military strike on fentanyl labs in Mexico would “destroy all the security cooperation between Mexico and the United States,” saying he considered it unlikely.

Still, the issue persists in the Republican primary. A NBC News poll released in June found 55 percent of all voters and 86 percent of Republican primary voters said they would be more likely to back a candidate who “supports deploying the U.S. military to the Mexican border to stop illegal drugs from entering the country.” Public opinion of sending American forces into Mexican territory has not widely been tested in recent surveys.

“There is no magic wand, military or otherwise, that the U.S. government can wave and make this problem go away,” said Brian Finucane, a senior adviser at the International Crisis Group. “The danger is that they risk normalizing the idea that the use of force is an appropriate policy response, and given the weak practical guardrails on the president, they make ideas that should be clearly off the table on the table.”

In addition to a naval embargo, Trump said he would designate cartels as terrorist organizations and order the use of Special Forces, cyber forces and covert actions. “President Trump was the first one to propose an aggressive plan to dismantle the criminal trafficking networks that are destroying lives and communities on both sides of the border,” campaign spokesman Steven Cheung said. “Biden has destroyed the border. President Trump will destroy the cartels.”

DeSantis brushed back at criticism from López Obrador in remarks to reporters over the weekend. “If he honestly wanted to get things right, he should be welcoming our support to try to stop what the cartels are doing,” he said. “We need to have a more modern version of a Monroe Doctrine,” he added, referring to 1823 declaration by President James Monroe that foreign powers should respect U.S. hegemony in the Western hemisphere.

At campaign stops, DeSantis said he would deploy deadly force at the southern border, leaving drug traffickers “stone cold dead.” The super PAC supporting him followed up with a video ad and merchandise using the catchphrase “stone cold dead.”

DeSantis elaborated on his proposed rules of engagement in an August interview with NBC News. “They got the satchel of fentanyl strapped to their back, you use deadly force against them, you lay them out, you will see a change of behavior,” he said. “You have to take the fight to the cartels otherwise we’re going to continue to see Americans dying.”

In the first Republican primary debate, DeSantis said he would send Special Forces over the border “on day one.” A campaign spokeswoman later suggested he was not speaking literally about deploying troops into Mexico territory as soon as Inauguration Day.

Ramaswamy, a long-shot first-time candidate who started voicing the idea of military force against Mexico on the campaign trail, has repeatedly compared an offensive there to the actions against terrorists in the Middle East. “I am yet to get a good answer from anyone on why we can’t just do this to solve the cartel problem and fentanyl problem,” he said in a February social media video. His campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Other Republican candidates such as former United Nations ambassador Nikki Haley and Sen. Tim Scott (S.C.) have expressed support in sending Special Forces, ground troops or drones into Mexican territory. Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and former Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson have advocated for deploying the military to the border while pressuring Mexico to police its own territory. Former vice president Mike Pence has said he would send Special Forces in partnership with Mexican forces.

U.S. authorities have said most fentanyl comes into the country through legal ports of entry rather than the desert gaps between border crossings, and those detained with the drug are far more likely to be U.S. citizens rather than migrants. In recent years, drug traffickers have become more entrenched in Mexican communities. Their organizations have diversified into extortion, domestic drug sales, illegal timber-cutting, sex trafficking and other illegal businesses, earning fortunes and employing thousands of workers.

The traffickers have long had ties to Mexican politicians and security forces, and those appear to have only strengthened as they expand their territorial control. The traffickers “are groups that provide votes, move votes and provide campaign financing,” Ernst said.

The U.S. government for years backed a strategy of targeting Mexican narcotics kingpins like Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman. While many were captured, the drug trade continues to flourish, in part because of strong U.S. demand for cocaine, methamphetamines and heroin.

It is particularly difficult to stop fentanyl trafficking because labs are small and can be located indoors. They do not emit heat signatures or smelly fumes, as methamphetamine labs do. Fentanyl is also highly concentrated and can be smuggled over the border in a backpack or suitcase, or hidden in truckloads of fruit or other products.

Mexico has reported growing seizures of fentanyl at roadblocks, package delivery offices and other sites. It said it captured 1,700 kilograms of fentanyl in the first half of the year, nearly as much as in all of 2022. But it has busted few fentanyl production labs.

U.S. officials and analysts differ over whether the failure to find more labs reflects a lack of political will or capacity. Mexico spends only around 1 percent of its GDP on security, less than most industrialized countries. Its security forces lack investigative authority, and the justice system has a poor record of securing convictions.

López Obrador has blamed the fentanyl problem on U.S. demand for drugs and Chinese production of precursor chemicals. The U.S. government said Mexico overtook China in 2019 to become the top producer of the deadly drug for the American market.

Unilateral military action could be costly for the United States. Mexico is its top trading partner and has played a key role in controlling the flow of migrants headed for the southern border. “It’s not like Mexico doesn’t have leverage here, including through migration and near-shoring and energy,” Ernst said. Near-shoring refers to moving offshore manufacturing to Mexico from more distant locations such as China.

Some Republicans, notably Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas, have pointed to the U.S. military’s anti-drug cooperation with Colombia as a possible model to curb. But the Mexican army has long been wary of the U.S. armed forces in part due to American military invasions in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tensions flared after the former Mexican defense minister, Salvador Cienfuegos, was arrested in 2020 in Los Angeles on drug charges. The Trump administration ultimately dropped the charges, citing the importance of the bilateral relationship, and Cienfuegos returned home. The Mexican military has grown more powerful under López Obrador, who has given it additional responsibilities such as running airports and building railroads, as well as battling drug traffickers.

“The Mexican military will not accept gringo overlordship,” said Federico Estévez, a Mexican political scientist. He noted that Cienfuegos had appeared at a recent Mexican military ceremony. “They stood him front and center,” he said. “The message is clear.”

Sheridan reported from Mexico City.