Perhaps one could argue that Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s prominence is unrelated to his last name. Maybe, had he been born Robert F. Stevenson, he would still have become a well-known activist who eventually tipped over into conspiracy theories and anti-vaccine activism.

But then perhaps the advertisement that aired during Sunday’s Super Bowl promoting Kennedy’s long-shot independent challenge to President Biden would have focused a little bit less on his last name.

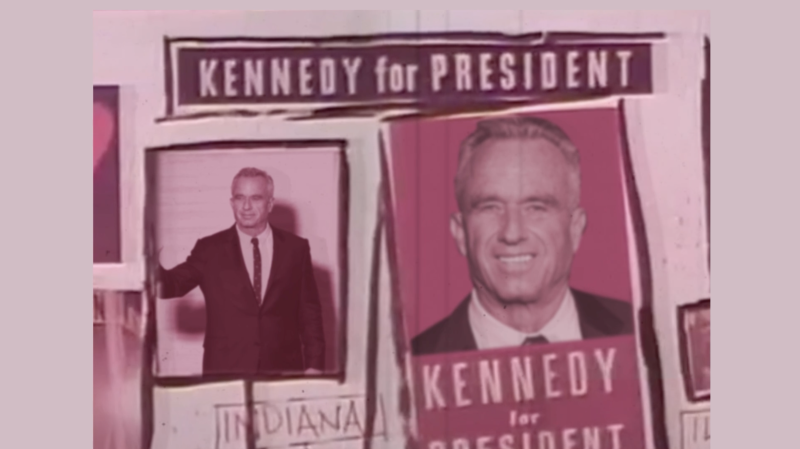

If you saw the ad when it aired during the first half of the game, you almost certainly understood that it was appealing to some form of Kennedy nostalgia. The obvious inspiration was an ad run by the campaign of Kennedy’s uncle John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential campaign.

Many of the illustrations and most of the lettering were lifted from the 1960 version, as was the song. There were important differences. Instead of saying “vote Democratic,” for example, the new version suggested that viewers “vote independent” — with the exception of one lingering “vote Democratic” that was written in small letters on a sign. But the drumbeat of “Kennedys” was preserved.

On the surface, it’s an odd gambit. Only about 3 percent of current U.S. residents were old enough to vote in 1960; presumably not a whole lot more remember the Kennedy era enough to have nostalgia for it. But, then, a Gallup poll conducted last year found that 90 percent of American adults view JFK’s presidency favorably, so why not tap into that sentiment?

Particularly since the ad wasn’t made by the Kennedy campaign, such as it is.

Instead, it was a product of a super PAC called American Values 2024. If you had never heard of this organization before, you are not alone. It has existed for less than a year; in 2022, the PAC was called the “People’s Pharma Movement.” Its parent organization focuses on spreading anti-vaccine rhetoric in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Tony Lyons, a representative of American Values 2024 (and co-founder of the People’s Pharma Movement), confirmed to CBS News that the group spent $7 million on the Super Bowl spot. That’s a lot of money, at least to most people.

But American Values 2024 has been the beneficiary of substantial contributions, including millions from billionaire Timothy Mellon (of the Mellon Mellons). He has a history of contributing to political initiatives he thinks are important, such as giving millions to an effort to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. Mellon also gave tens of millions to PACs backing Donald Trump’s 2020 reelection bid.

Outside spending on behalf of a candidate is referred to as independent expenditure. There are strict rules governing such spending, notably that committees engaged in independent spending cannot coordinate with candidates. After all, if they could, the independent efforts could simply raise unlimited money that the candidate could direct, obliterating campaign-spending rules.

Usually, independent expenditures do what American Values appears to have done here, spending money on efforts to promote candidates that such groups think are going to be useful. At the very least, the ad did trigger a sudden surge in search interest focused on Kennedy — though well below searches for Biden at his peak last week and, in the hours after the ad, well below both Trump and Biden.

During this election cycle, an independent-expenditure effort went further. Much of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s bid for the Republican nomination was driven by a PAC called Never Back Down. The result was a great deal of public fighting, an enormous amount of money spent and an embarrassing finish for the candidate.

It is not always the case that spending by outside groups aims solely to boost candidates, of course. In the case of American Values 2024, there are certainly some participants, like Lyons, who have long-standing relationships with the candidate and seem invested in his election.

But if you were a billionaire interested in boosting an alternative to Biden among people who, say, view JFK with nostalgia? A PAC like American Values would be a good place to park $10 million or so.

From the standpoint of the campaign, the independent spending for the Super Bowl spot let Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have his cake and eat it, too. Soon after the spot ran and American Values shared it on social media, Kennedy shared it as well. If you visit Kennedy’s page on X (formerly Twitter), the independent ad is his pinned — that is, featured — post.

As of writing, the post that appears immediately under the pinned post is one apologizing for the ad.

“I’m so sorry if the Super Bowl advertisement caused anyone in my family pain. The ad was created and aired by the American Values super PAC without any involvement or approval from my campaign,” it reads. “FEC rules prohibit Super PACs from consulting with me or my staff. I love you all. God bless you.”

See, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is not the only inheritor of the political power of the Kennedy dynasty. Cousin Bobby Shriver (whose mother, Eunice Kennedy, was Robert F. Kennedy Sr.’s sister) blasted the ad as exploiting images of the family in service of the candidate’s political views.

My cousin’s Super Bowl ad used our uncle’s faces- and my Mother’s. She would be appalled by his deadly health care views. Respect for science, vaccines, & health care equity were in her DNA. She strongly supported my health care work at @ONECampaign & @RED which he opposes.

— Bobby Shriver (@bobbyshriver) February 12, 2024

His well-known sister, journalist and former California first lady Maria Shriver, shared his sentiment with her followers on the platform.

But Robert F. Kennedy Jr. contends that it’s not his fault. He gets the boost in attention and the intertwining of his candidacy with his uncle’s — and gets to pass the blame on to American Values.

American Values also gets a boost in attention for itself and for Kennedy, a boost that might make the independent candidate more appealing to people skeptical of both Biden and Trump. And all for the price of 0.05 percent of the Mellon family’s estimated net worth.