A bipartisan group of tech critics on Tuesday morning launched the “No Big Tech Money” pledge, an effort to curb Silicon Valley’s influence over 2024 candidates.

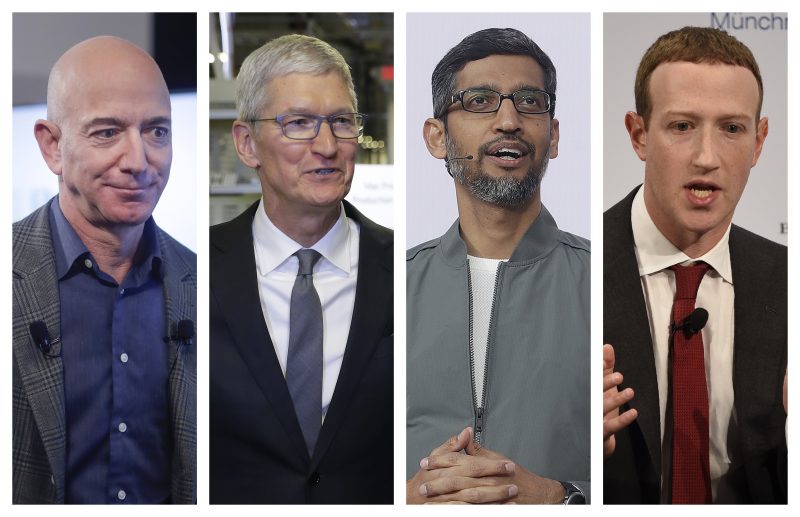

Candidates who take the pledge agree not to take donations of more than $200 from the political action committees, executives or lobbyists of Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google parent company Alphabet or Facebook parent company Meta. The initiative, which received initial funding from the liberal organization Way to Win, wants to attract signatures from candidates running for the White House and Congress from both political parties. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post. Interim CEO Patty Stonesifer sits on Amazon’s board.)

The organizers want to draw attention to the influence that large tech companies have over the U.S. economy and political processes.

“The pledge is a way for politicians to say enough is enough and to signal to voters that they’ll put our democracy, our small businesses and our families over Big Tech’s corrupting influence,” Emily Southard, executive director of The No Big Tech Money Project, said in an interview.

Silicon Valley companies have emerged as some of the most potent corporate forces in Washington over the past decade. The pledge is the latest sign of efforts to challenge the industry’s maturing influence; activists have previously taken a similar tack to challenge fossil fuel, pharmaceutical and lobbying interests.

The internet industry spent about $106.2 million on campaign donations in 2020, according to the nonprofit Open Secrets, up nearly three times from its total in 2016. The vast majority of those contributions went to Democrats. The top recipient in 2020 was President Biden, who received $13.5 million from the industry during his White House bid.

The group’s board is composed of several prominent tech critics from both political parties. Dan Geldon, who served as chief of staff for Elizabeth Warren’s presidential bid, and Jeff Long, an attorney who has previously advised Republican senators and the FTC, serve alongside Sacha Haworth, the executive director of the anti-monopoly Tech Oversight Project.

The tech-focused pledge is modeled after the “No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge,” which attracted signatures from thousands of Democrats running for the White House, Congress and local offices. Yet such pledges can be challenging to enforce, as federal filings show that campaigns often accept donations from people in those industries — as long as their titles fall outside of the narrow definitions in the pledge.

The No Big Tech Money coalition says it will be unable to monitor all contributions accepted by candidates, but if it is notified of violations, it will remove pledge signers unless they return the donation within a week.

The pledge focuses specifically on the five companies that would be covered by the American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICOA), an antitrust bill that seeks to limit tech companies from giving their own products a leg up over their competitors. AICOA and a package of other tech competition bills failed to pass Congress following an extensive lobbying campaign by industry.

“We’ve been faced with this mountain of spending, and if we’re going to be successful in taking on and confronting the influence that big tech money has on our political system, we need to do what other issue areas have done,” Haworth said.

The pledge does not apply to many tech companies that have long been influential in politics, including Netflix, Oracle and Twitter.

This differs from the fossil fuel campaign in its bipartisan approach, as prominent Republicans are critical of the tech industry. Presidential candidates Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis have both attacked major social media companies on the campaign trail, frequently accusing them of censoring their political views.

“Many of the Republican contenders in the primary would at least consider it,” said Aiden Buzzetti, the president of the conservative-leaning Bull Moose Project.