“My father, Charles Tuberville, made the D-Day landing at Normandy as a tank commander with the 101st infantry. He served with honor during World War II, earning five Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart.”

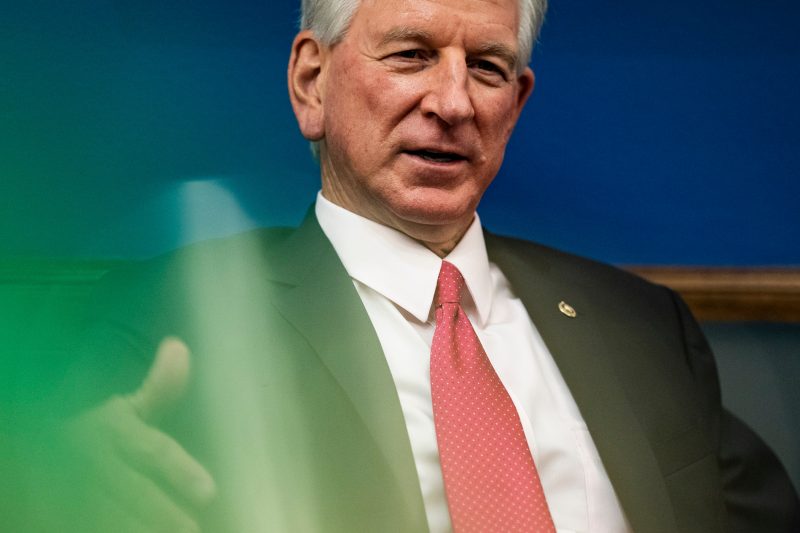

— Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.), in a tweet posted with a Fox News interview, June 6

“He lied about his age at 16, joined the Army.”

— Tuberville, in the Fox interview

“He was a tank commander with the 101st Infantry and landed at Normandy Beach on D-Day and drove a tank through the streets of Paris when the U.S. forces liberated the city.”

— Tuberville, on the archived website of the Tommy Tuberville Foundation

For nearly a decade, Tuberville has described the World War II exploits of his father, Charles R. Tuberville Jr., in a relatively consistent way — that he was a tank commander, that he earned five Bronze Stars, that he participated in the D-Day landing and that he lied about his age to join the army. News organizations have tended to accept Tuberville’s version and either reprint or broadcast it.

Yet an examination of army histories, newspaper reports and other materials calls into question many of the claims put forth by Tuberville, who sits on both the Senate Armed Services and Veterans’ Affairs committees and is now in a high-profile battle with the Biden administration over a Defense Department policy offering time off and travel reimbursement to service members who need to go out of state for abortions. Since February, he has blocked every personnel move in the U.S. military that requires Senate confirmation, stalling the promotions of more than 265 senior military officers. The Pentagon has said Tuberville’s holds are putting the nation’s military readiness at risk, as 650 general and flag officers will require Senate confirmation by year’s end.

In effect, Tuberville has promoted his father to highly decorated tank commander — but based on our research, that claim is dubious.

Family histories often include myths or stories that become exaggerated as they are handed down from generation to generation. Most of the Army personnel records from World War II were destroyed in a 1973 fire, making confirmation difficult. There is no doubt that Tuberville’s father faced difficult and dangerous combat under trying conditions, including during the Battle of the Bulge, the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes. We are not questioning his heroism or service.

So we will not be issuing a Pinocchio rating but instead will highlight what elements of the senator’s story raise questions or are inaccurate — and which ones appear to be correct. Steven Stafford, Tuberville’s communications director, responded to our questions by quoting from what he described as Charles Tuberville’s “report of separation” from the Army but, except for a snippet, declined to provide a copy for review by The Fact Checker.

This is false. Charles Tuberville, who was born in 1925, turned 16 five months before the United States entered World War II because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His draft registration card (front and back) shows he submitted it on July 16, 1943 — his 18th birthday.

That was required under the law, according to the card, which states it is “for the registration of men as they reach the 18th anniversary of the date of their birth.” (The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 had required registration upon the age of 21, but Congress amended that to 18 after the United States entered the war.) Voluntary enlistments were eliminated in November 1942, so every soldier was drafted. Tuberville’s Veterans Affairs records state that he was enlisted into the Army on Nov. 8, 1943. Both his card and the VA records show he was honorably discharged on Dec. 27, 1945.

Stafford did not respond to questions about this claim.

This is dubious. Charles Tuberville’s tombstone lists his highest rank as “TEC 5” or technician fifth grade, an Army rank at the time that indicated technical skills but not combat leadership. According to a 1944 Army memo, TEC 5 jobs were limited to armorer, cook, tank driver, light truck driver or tank mechanic. Tuberville would have needed to be a sergeant to be a tank commander.

That said, it’s possible that at some point in the war as a TEC 5 he commanded a tank if the unit was strapped for leaders, and he was deemed capable enough by his superiors.

While Tuberville’s promotion record is unclear, the Camden (Ark.) News reported on Feb. 7, 1945, that he had been promoted to corporal. (TEC 5 was at the corporal level.) That makes it even more unlikely that he was a tank commander on D-Day.

Stafford said the report of separation showed Charles Tuberville was a TEC 5 in World War II.

This is possible. Tuberville was a member of the 746th Tank Battalion (A Company), according to a statement placed on a memorial website by his widow, the late Olive Nell Chambliss, and official Army after-action reports of the battalion. After being afloat off the coast of France from June 1 to 5, A Company began landing on Utah Beach on June 6, and by June 8 one platoon had brought four tanks ashore, the reports say. The company connected with the 101st Infantry in the days after the invasion, so the senator’s reference to the 101st is accurate.

The Army history makes clear the dangerous and bloody toll the invasion took on the battalion, with page after page listing the dead and wounded. When a violent rainstorm hit France on July 1, the report notes: “For many officers and men this provided the first opportunity since 6 June to remove their shoes, their chemically impregnated clothes and to bathe. No showers were available but improvised bathing facilities were introduced.”

Whether Tuberville’s father participated in the invasion is unclear. He is not mentioned in any of the after-action reports until he appears on a list of wounded in April 1945, 10 months after D-Day.

The Camden News reported that Tuberville had been “overseas since June 7, 1944” — the day after D-Day. Because so many replacements were needed to fill in for the hundreds of soldiers who were killed, wounded or sick, it would not have been unusual for someone to have joined the battalion after the invasion of France. In fact, in a 2008 interview with ESPN, Tuberville said his father went into Europe days after D-Day — not on D-Day.

Stafford said the report of separation said Tuberville was part of the 746th Tank Battalion (A Company) and his date of arrival in theater is listed as June 6, 1944.

This is true. This decoration is awarded to soldiers killed or wounded while serving. The Army reports show Tuberville was wounded on April 15, 1945, when enemy bazooka fire hit a tank, killing one person and wounding three. Tuberville, identified as a TEC 5, is listed as LIA — which is military code for “lightly wounded in action (hospitalized).”

The Camden News reported that his parents received a letter saying he was wounded in Germany and was recovering in a hospital in France. His tombstone and his widow’s memorial notice both say he was awarded a Purple Heart. Stafford said the report of separation said Tuberville earned a Purple Heart.

This is false. The Bronze Star, the eighth-highest military award, is earned when a soldier “distinguished himself or herself by heroic or meritorious achievement or service” in combat with an armed enemy of the United States.

Earning five Bronze Stars would be highly unusual; Audie Murphy, the most decorated soldier of World War II, earned two Silver Stars and two Bronze Stars, among other medals. About 395,000 Bronze Stars were awarded to the 11,200,000 Army soldiers who fought during World War II, so about three out of every 100 soldiers earned one.

None of the hundreds of pages of after-action reports on the 746th Tank Battalion, from June 1944 to August 1945, lists Tuberville as a recipient of the Bronze Star even as the reports meticulously list scores of soldiers who were either recommended for an award or received one.

Neither his tombstone nor his widow’s memorial notice makes any mention of Tuberville’s earning a Bronze Star, let alone five.

Stafford provided a photo of a snippet of the report of separation that said Tuberville was “awarded 5 Bronze stars for above campaigns per WDGO #33-40 1945.” He said the report of separation referred to the Central Europe, Ardennes, Rhineland, Northern France and Normandy campaigns.

That photo snippet confirmed Tuberville earned not Bronze Stars, but rather Bronze service stars — which denote that a soldier was physically present during a particular military campaign or engagement. Campaign service stars, unlike the Bronze Star, are not individual medals and do not indicate valor in combat. The notation “WDGO #33-40 1945” refers to War Department General Orders 33 and 40, issued in 1945, which defined the dates of the campaigns.

An Army document says the Normandy campaign lasted June 6 to July 24, 1944; the Northern France campaign from July 25 to Sept. 14, 1944; the Rhineland campaign from Sept. 15, 1944, to March 21, 1945; the Ardennes-Alsace campaign from Dec. 16, 1944, to Jan. 25, 1945; and the Central Europe campaign from March 22 to May 11, 1945.

Army Pamphlet 672-1 (July 1961) confirms that Ardennes-Alsace, Central Europe, Normandy, Northern France and Rhineland were the campaigns in which the 746th Tank Battalion participated.

This is not possible. The Army’s 28th Infantry Division marched down the Champs-Elysées on Aug. 29, 1944. The after-action reports for the 746th Tank Battalion show that on Aug. 29 it was attached to the 9th Armored Division. The battalion that day crossed the Marne river, facing little resistance, before reaching a position astride the Aisne river, the report says.

In other words, Tuberville would have been about 90 miles northeast of Paris when the troops of the 28th Infantry Division made their triumphant march.

Stafford did not respond to questions about this claim.

(About our rating scale)

Send us facts to check by filling out this form

Sign up for The Fact Checker weekly newsletter

The Fact Checker is a verified signatory to the International Fact-Checking Network code of principles